This article follows a similar format as the analysis of ATB’s CEO compensation. We begin with some background on the creation of the corporation in 2007 from published and unpublished research. Then follows a series of charts illustrating the evolution of AIMCo CEO pay over the period. The concluding section investigates the question of pay equity by comparing the AIMCo chief’s compensation against the average compensation of AIMCo employees, peers- the Caisse de Depot et Placement du Quebec (Caisse), the British Columbia Investment Management Corporation (BCMIC), and senior elected and appointed provincial officials.

A slide deck is included at the bottom of this article.

Background

In 2007, the Alberta Investment Management Corporation Act was passed creating a board-governed provincial corporation that would manage approximately $65 billion in government assets and public sector pension plan assets. The evolution of the Alberta Investment Management (AIM) group, inside the Province’s Finance department, into a provincial agency followed. To some extent, the model of ATB’s corporatization project in 1997 was followed in that it emphasized independence from government (politicians and bureaucrats) and “market” levels of compensation. By the dawn of the millennium, the principal challenges facing AIM was attracting and retaining staff and receiving government funding to upgrade investment management systems and software.

To prepare the groundwork for the corporatization of AIM, a report by Capelle Associates was commissioned to study whether the current organization structure was “optimal.” A range of disadvantages was listed. The Report’s main conclusion was to corporatize both the investment management and investment administration groups in the Treasury/Finance department. With a board exhibiting the “appropriate accountabilities and authorities” selected, the board would hire a CEO who would determine a risk management framework, establish performance targets, review performance, and “ensure an optimal organization design including compensation” (emphasis added).

Part of the Capelle Report’s rationale for corporatization was the expectation the new entity would “add value” through its expertise in active investment management. Even a basis point improvement on $65 billion would mean $6.5 million.

AIMCo was to become a stand-alone entity with a “qualified board” to guide its early development. Significantly, the board had no representatives from the large public sector pension boards such as the Local Authorities Pension Plan (LAPP).

As with ATB’s early evolution, once the board was created its first step was to hire a Chief Executive Officer. After an international search, Leo de Bever, the former head of the Victoria State Pension Plan, was appointed. It was an inauspicious start for de Bever who arrived during the Global Financial Crisis.

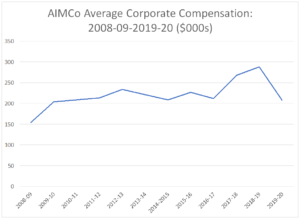

As in the case with ATB Financial, average income of AIMCo employees increased significantly as shown in the figure below. Starting at an average of about $150,000, compensation steadily rose to hit $234,000 in 2012-13. Average salary is computed by taking the FTEs as reported by AIMCo and dividing into total compensation (salary and benefits). Since AIMCo did not always report their FTE numbers in annual reports, the FTE number is based on estimates included in the Province’s annual Fiscal Plan. The averages are sensitive to the number of employees hired during the year and short-term incentive plan bonuses. After 2012-13, average compensation stabilizes then increases in 2017-19 and 2018-19. These are excellent compensation packages when compared to the Alberta public service.

Transparency

In November 2015, the New Democratic government proposed new legislation to improve transparency for public sector compensation. Bill 5 was originally designed to be comprehensive but there was resistance from financial agencies like ATB, Alberta Teachers’ Retirement Fund (ATRF), and AIMCo. These entities who sought exemptions on the basis that their “underpaid” talent could be poached by head-hunters. When the Act was proclaimed in early 2016 AIMCo, ATB and the ATRF non-executive employees were exempted in the interests of preventing this form of poaching. In contrast, other high paying agencies such as the Securities Commission, the Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission, the Alberta Utilities Board, the Balancing Pool, and Alberta Electric Systems Operator were not exempted. The newly formed Notley government did not push back proposing for example that salary ranges be used for these highly paid and trained financial analysts. This reticence perhaps was based on an assumption, accepted by the Notley government, that highly paid staff were actually paid lower than comparable positions in the private sector. Whether these claims were valid remains an open position because turnover rates at ATB and AIMCo are not available to analyze such claims.

Challenges to Evaluation

While ATB now aims to earn a risk-adjusted rate of return comparable to its competitors, AIMCo’s role is to add value to pension funds through active investment management. AIMCo’saudied financial statements reveal only a limited flow of funds from clients paying for AIMCo’s services. At the end of March 2020, AIMCo had net assets of $3.6 million and revenue and expenditure of $482 million showing its operations were cost recovery.

Since AIMCo is a cost recovery operation, evaluating the CEO’s performance is based on the metric of investment returns generated by AIMCo’s active management exceeding “appropriate” benchmarks. This leads into the murky area of assessing what is the appropriate benchmark. In AIMCo’s case, this is problematic because each pension board writes their own statement of investment policy and they set out what that board believes would be an appropriate expectation for exceeding the benchmark chosen. In the case of AIMCo compensation however, the measurement of value added in excess of the benchmark is done for the corporation and investment portfolios managed by AIMCO as a whole, which seems reasonable.

In order to address this, we look at the performance of AIMCo from the vantage point of the overall returns as published in annual reports. We note that the 2008-10 period, because of the effects of the Global Financial Crisis and the fact that the CEO “inherited” the investment portfolio and portfolio strategies, no immediate judgement should be made of the then CEO’s performance. The comparison following is at the aggregate pooled pension plan level rather than the baskets under the full plan (e.g. Canadian equities, international equities, private equity) nor at the individual pension plan level.

Comparisons

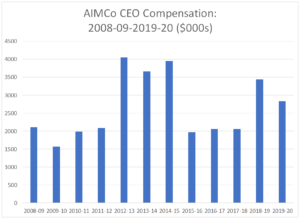

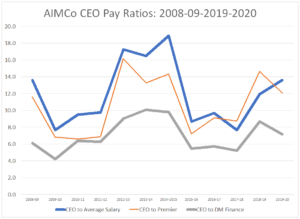

The chart which follows compares AIMCo CEO’s total compensation against the compensation of the deputy finance minister and the premier, and average AIMCo compensation The pay ratios have stayed fairly constant over time being generally higher under Leo de Bever’s tenure (2008-2014) than the current incumbent Kevin Uebelein. As with most new hires, the pay levels are lower and increase over time as more long-term incentive pay is added into total compensation figures.

However, is five, ten or 15 times the compensation of senior government comparisons warranted? Most Albertans and public servants would likely think not- certainly not public sector unions.

There has been an aura build up about financial services’ jobs, particularly in investment management, whereby these individuals have been able to command high salaries especially during the 2000s. Given the groupthink that went prior to the Global Financial Crisis, it remains surprising that despite the failure of financial analysts, CEOs and chief investment officers to recognize the housing and debt bubble looming in 2006-07, financial expertise is still looked upon in a reverent awe.

Comparison to Peers

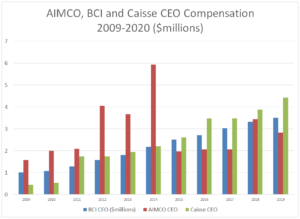

In the following charts we compare AIMCo CEO’s compensation against that of the CEO of the Caisse de Depot et Placement du Quebec (Caisse) and the British Columbia Investment Management Corporation (BCI). These two corporations are very similar to one another because they each have a significant number of clients (Caisse -40 ; BCI- 31; AIMCo- 31), their mandates are similar to the extent they manage large public sector pension funds and other funds, and compete in the same investment management talent pool.

Several issues stand out from this simple comparison. First, the high remuneration in 2014 reflects a transition between de Bever and Uebelein. In 2014, the total includes the estimated future pay-out to de Bever who ceased employment on December 31, 2014. The compensation of the CEO for the Caisse CEO, Henri-Paul Rousseau, reflects the significant losses taken by the Caisse during the global financial crisis. The Caisse had similar problems as ATB Financial- large holdings of Non-bank asset-backed commercial paper. Also of note, is the steady climb in the compensation of the BCI CEO, who in the early part of the period was paid considerably less than his AIMCo counterpart. AIMCo’s pay since Uebelein has taken over is more in line with his counterparts.

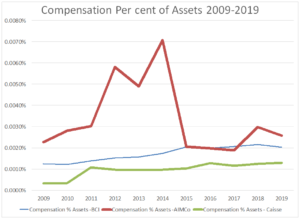

In the chart below, our next set of comparisons is compensation of the CEO as a percentage of year-end assets under management (AUM). By this measure, AIMCo compensation levels do not appear to be related to the assets under management. Certainly, these numbers speak little to the value produced by the investment manager, which is explored further below. In the case of the both the Caisse and BCI CEOs the relationship between AUM and is fairly constant whereas AIMCo’s is more variable. This could reflect the fact that the first several years were periods when the organization was being transformed from a government function to a stand-alone agency. Since 2014, the relationship between AUM and compensation has been more stable although AIMCo still pays a slight premium when comparing this metric. Conceivably this is the “Edmonton premium” – paid to attract the best candidate to the northern capital

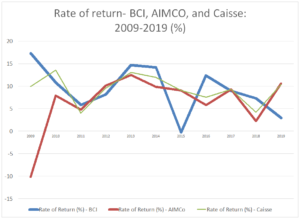

Next we compare the overall rates of return of these investment managers. In the case of BCI the rates of return are for years ending March 31st– in the case of the Caisse and AIMCo, they are on a calendar year basis. With the exception of 2015 for BCI, the rates of overall return (nominal) are similar. Note there was not one year that AIMCo’s overall rate of return was higher than both of its peers. However, this is not definitive.

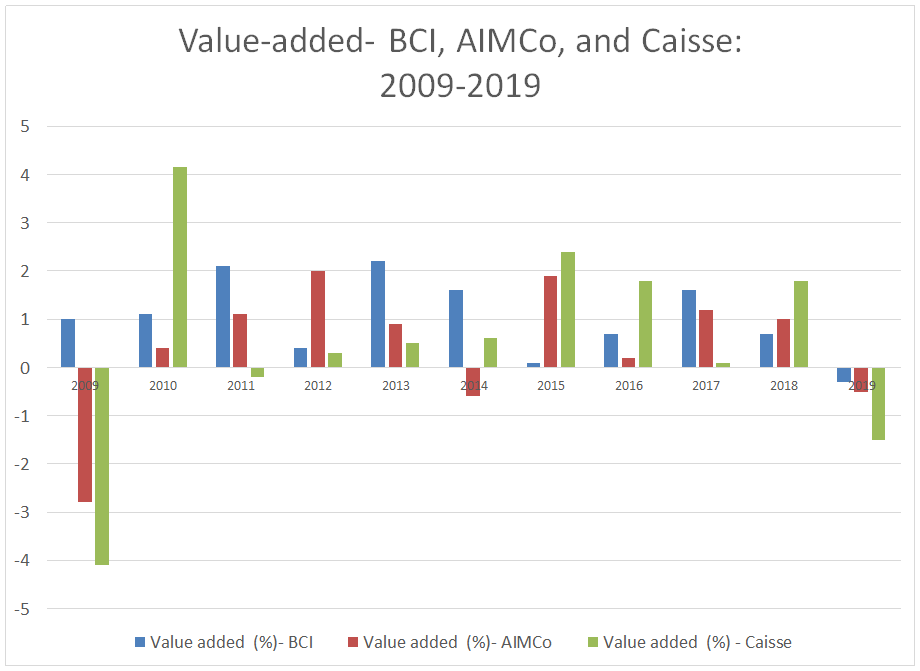

In the following figure we contrast return performance against benchmarks used in the annual reports. The Caisse seemed to have accidents every decade while BCI appears to manage downdrafts better but this may be an artefact of timing and one-year returns are inadequate to determine value added.

A further way of evaluating the value add of an organization, as opposed to the CEO, is to take the average percentage value-added over the 11-year period. In AIMCo’s case it is 0.44 per cent, BCI- 1.02 per cent, and the Caisse – 0.53 per cent. Looking at the Uebelein years versus the de Bever years reveals that the value added by Ubelein outpaced de Bever by an significant extent: from 2008-09 to 2014, de Bever’s value added was -0.17 per cent, whereas Uebelein’s has been a positive 0.76 per cent. Comparing the same periods yield the same results directionally. The past half decade has been more benign, shall we say, for these Canadian public fund managers. Obviously we shall how 2020-21 turns out- a period of extreme volatility and unpredictability in equity, private equity, fixed income, real estate, and fixed income markets.

AIMCo CEO pay is set in the context of human capital markets. Whether the pensioners are getting satisfactory value from an active investment strategy as opposed to a passive strategy is a question debated in investment management literature. A key goal of creating AIMCo ws to repatriate some of the active investment portfolios to Alberta. At the present time, there is a major push by an advocacy group called Shaping Alberta’s Future. A key part of the Alberta separatist chat follows the Quebec Inc. model. The Caisse, the brainchild of Jacques Parizeau when he was Quebec’s deputy finance minister, maintained a critical mass in investment management as key Anglo institutions slowly departed.

The model now followed by the UCP government is to gain as much control of large pools of public sector pension assets and WCB investments to increase opportunities for high quality jobs for Albertans. However, what is worrisome is the penchant of the Kenney government to restructure the Alberta Teachers’ Retirement Fund and WCB without consulting the affected organizations. Equally disturbing is the facile manner that this advocacy group promotes the promise of lower premiums as the most important facet of such a takeover.

Source: Edmonton Journal, 17 November 2020

Today it seems a foreordained conclusion that the government, based on “expert advice,” will recommend an Alberta Pension Plan. It will be interesting to see how strongly the report addresses full operational independence from the government and whether or not representatives of the pension funds will be given seats at the governance table. If independence is not guaranteed, that is a cue for Albertans nearing a decision to draw their CPP to consult their financial advisors about the advantages and disadvantages of an Alberta Pension Plan.

In a forthcoming article, we examine the quality of compensation disclosure at ATB Financial and AIMCo.

Slide Deck and Related Posts

AIMCo-CEO-Compensation

Hello. impressive job. I did not anticipate this. This is a splendid story. Thanks!

Good article Bob.