Updated 15 November 2023

Overview

In the dissent, Justices Karakatsanis and Jamal pose a certain fact situation eerily akin to what happened with a leaking tailings pond and potential for justice for indigenous groups living downstream. If this is eerily similar to the case of First Nations living downstream from the Kearl Lake tailings ponds owned by Imperial Oil, it is. Boiled down into its most essential is the value of people vs.the value of things. Do we value a life more than say $20-billion in bitumen royalties and billions more in personal and corporate income tax ?

Justice Andromache Karakatsanis Source: The Canadian Encyclopedia

To give a concrete example, on the majority’s view, there is (properly) no constitutional objection to federal authorities prohibiting a nickel refinery in a province — a provincially regulated project — which has substantial economic benefits that are outweighed by substantial environmental harms to Indigenous peoples, Indigenous lands, or the rights of Indigenous people protected under s. 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 because such harms are adverse federal effects under the IAA. But, on the majority’s view, if the same project caused less substantial but still significant harm to Indigenous interests (thus triggering an adverse federal effect), federal authorities could not constitutionally prohibit the project on the basis that it might cause cancers or respiratory diseases to non-Indigenous peoples in neighbouring communities, because this would be to consider a constitutionally impermissible non-federal effect. To quote La Forest J. in Oldman River, this approach “defies reason” (p. 66).

Justice Mahmud Jamal Source: Canadian Immigrant

Soon after the Court’s opinion on the reference case, Premier Smith and her justice minister Mickey Amery issued a news release which claimed, in part:

The decision is also a massive win for the protection of sovereign provincial rights under the Constitution. The federal government, through passage of Bill C-69, and continuing now with their proposed electricity regulations and oil and gas emissions cap, is blatantly attempting to erode and emasculate the rights and authorities of provinces as an equal order of government under the Canadian Constitution. Today’s court decision significantly strengthens our province’s legal position as we work to protect Albertans from federal intrusion into various areas of sovereign provincial jurisdiction. Alberta will continue to partner with other willing provinces and interveners in pushing back against these unconstitutional federal efforts using all legal means available to us.

The majority opinion was authored by Chief Justice Richard Wagner with the majority consisting of three justices from Quebec (Wagner, Honourable Suzanne Côté, and Honourable Nicholas Kasirer) and Justice Sheilah Martin of Alberta and Justice Malcolm Rowe from Newfoundland and Labrador).

Main Take-aways

This was a pro-development judgment. Senior business leaders in this country from banks to manufacturers to extractors have joined in chorus and have been pushing the federal government hard to streamline major private sector investment projects including mines, pipelines, and roads. This judgment re-balances the economic with the environment. Business groups are predictably delighted while environmental organizations have been more sanguine.

Regulatory certainty is essential to generate investment and growth in our nation. The ambiguity surrounding the interaction between federal and provincial regulatory bodies has created a climate where businesses face heightened risks and reduced confidence in Canada’s regulatory processes.

Canadian Chamber of Commerce- 3 October 2023

Today’s decision from the Supreme Court, while ruling that parts of the Impact Assessment Act are unconstitutional, still affirms that the federal government does have jurisdiction to review projects to ensure that environmental impacts are avoided or mitigated. This is good news.

Environmental Defence 13 October 2023

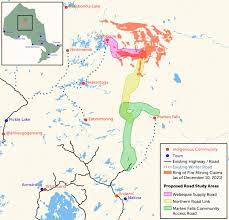

Since this written decision is “only” an opinion on a reference on the constitutionality of the Impact Assessment Act, the status quo holds until the federal government amends the Act. Notably, the review of Highway 413 in Ontario’s Ring of Fire is expected to continue which poses a threat to Premier Ford’s desire to attract investment into this region.

Ontario’s Ring of Fire Source: The Narwhal

Federal Environment Minister Stephen Guilbeault and Justice Minister Arif Virani released a short statement in response to the Court’s decision. In this statement the ministers stated they “will now take this back and work quickly to improve the legislation through Parliament.” Note the official federal government announcement did not include Natural Resources minister Jonathan Wilkinson. It’s now in the hands of Justice and Environment and Climate Change Canada, although this may be subject to change. Natural Resources and Finance Canada are formidable opponents to cutting production as the oil and gas industry remains a key cash cow for the federal government. Note this source- the Canadian Energy Centre is not without bias but states its numbers come from Statistics Canada and CAPP. Nevertheless the quantum, which is no doubt exaggerated sends a very clear signal to federal bureaucrats and federal politicians (provincial politicians already no this- especially in western cabinet rooms).

The war between the Attorney General of Alberta and the Attorney General of Canada is far from over. Alberta has already challenged the federal government authority’s to regulate emissions even before the recent reference case decision, with Smith stating that “Ottawa has no constitutional authority to regulate in these areas of exclusive provincial jurisdiction.” She added “We would strongly suggest the federal government refrain from testing our government’s or Albertans’ resolve in this regard.”

The statement affirmed the federal government’s intention to work co-operatively with the provinces, noting the court was explicit in “affirming the right of the Government of Canada to put in place impact assessment legislation.” Notable in the statement was Ottawa’s recognition that it must “create a better set of rules that respect the environment, Indigenous rights and ensure projects get assessed in a timely way.”

The opinion recognizes the “abstruse” nature of environmental regulation in this country where the impugned federal statue clashes with provincial jurisdiction over the ownership and management of natural resources (Section 92A of the Constitution Act.)

Just as Justice Greckol’s dissent identified the issue of vast increases to in-situ bitumen production if the Government of Alberta’s regulatory system exclusively approved expansions, we have now the future problem of whether resource development trumps the health of First Nations. Put bluntly this decision would give the regulator and the industry full authority to affirm support for any policy that is tantamount to genocide on indigenous communities downstream from the massive oilsands developments around Fort McMurray.

The majority opinion and the dissenting opinion both rely on a recognized juridical approach to matters of constitutional law. The Court asked itself two basic questions- 1) what is the “pith and substance” of the legislation or its purposes. This is called characterization. The second step us to determine the classification of the legislation according to the various sets of powers assigned to the federal government and the provinces.

Majority Opinion

The majority opinion begins reviewing the evolution of environmental assessment legislation (paras. 9-31) and the legislative schema of the IAA (paras. 32-49) starting in 1973. The principle evolutionary development is a “dramatic shift” from a “decision-based trigger“ to an “effects- or project-based trigger.” In contrast the Alberta Court of Appeal (ABCA) judgment led with a discussion of the evolution of section 92A the resource amendment (text below). The architecture of the Act sets out three discrete phases: 1) planning phase culminating in a decision to designate a project (screening decision); 2) assessment or information gathering phase; and 3) decision-making phase.

Next Chief Justice Wagner considers the judgment of the ABCA. The opinion characterizes the regulatory regime as subjecting “all activities designated by the federal executive to an assessment of all their effects and federal oversight and approval,” and thus ““intrudes fatally into provincial jurisdiction and the provinces’ proprietary rights as owners of their public lands and natural resources” (emphasis mine). The ABCA majority also said the legislation did not fall under any heads of federal power including inland fisheries, imperial treaties, Indians and lands reserved for Indians, criminal law, and the peace, order and good government power. Rather, the province’s jurisdiction over development and management of natural resources and property and civil rights granted the province’s what I call primary jurisdiction.

Then follows the standard, accepted approach of first characterizing the pith and substance of the legislation- its purpose and then classifying under what federal or provincial powers the statute falls under.

Under characterization, the courts look at both the legal and practical or “side” effects of the legislative scheme. Characterization analysis does not refer to the division of powers. In considering whether to characterize a law there is a presumption of constitutionality but that does not constitute an “impermeable shield that protects legislation from constitutional review by courts” (para 73).

Wagner characterizes the IAA as a scheme to “to assess and regulate designated projects with a view to mitigating or preventing their potential adverse environmental, health, social and economic impacts.” Section 6 of the Act lays out the purposes of the legislation (see below).

6 (1) The purposes of this Act are (a) to foster sustainability; (b) to protect the components of the environment, and the health, social and economic conditions that are within the legislative authority of Parliament from adverse effects caused by a designated project; (b.1) to establish a fair, predictable and efficient process for conducting impact assessments that enhances Canada’s competitiveness, encourages innovation in the carrying out of designated projects and creates opportunities for sustainable economic development; (c) to ensure that impact assessments of designated projects take into account all effects — both positive and adverse — that may be caused by the carrying out of designated projects; (d) to ensure that designated projects that require the exercise of a power or performance of a duty or function by a federal authority under any Act of Parliament other than this Act to be carried out, are considered in a careful and precautionary manner to avoid adverse effects within federal jurisdiction and adverse direct or incidental effects; (e) to promote cooperation and coordinated action between federal and provincial governments — while respecting the legislative competence of each — and the federal government and Indigenous governing bodies that are jurisdictions, with respect to impact assessments; (f) to promote communication and cooperation with Indigenous peoples of Canada with respect to impact assessments; (g) to ensure respect for the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, in the course of impact assessments and decision-making under this Act; (h) to ensure that opportunities are provided for meaningful public participation during an impact assessment, a regional assessment or a strategic assessment; (i) to ensure that an impact assessment is completed in a timely manner; (j) to ensure that an impact assessment takes into account scientific information, Indigenous knowledge and community knowledge; (k) to ensure that an impact assessment takes into account alternative means of carrying out a designated project, including through the use of best available technologies; (l) to ensure that projects, as defined in section 81, that are to be carried out on federal lands, or those that are outside Canada and that are to be carried out or financially supported by a federal authority, are considered in a careful and precautionary manner to avoid significant adverse environmental effects; (m) to encourage the assessment of the cumulative effects of physical activities in a region and the assessment of federal policies, plans or programs and the consideration of those assessments in impact assessments; and (n) to encourage improvements to impact assessments through the use of follow-up programs. |

The examination of “extrinsic evidence” or background materials associated with process of policy making and legislation-making suggested that the “assessment process is designed to account for more than just the environmental effects of a proposed project“(para. 84). These effects, according to the then Environment Minister, could include ensuring “that potential impacts on “women, men, or gender-diverse people are identified and addressed” (para. 86). Another practical effect of the legislation was to give the federal executive branch decision-making authority over designated projects.

The legal effects of the legislation include, if a project I is designated, that the project is placed on a temporary hold pending the regulatory process. This practically means no physical activity can be undertaken (paras. 94-97). As in the ABCA majority opinion, Wagner noted that the scheme results in delays of indeterminate duration” (para 106).

When classifying a legislative scheme courts must reference the heads of power to determine if the law falls under the jurisdiction of the federal or provincial legislature. Some powers are assigned concurrently including section 92A(3). Classification is based on the “main thrust or dominant characteristic” of the law and not secondary effects (para. 113). Since environment is not an enumerated power in the Constitution, the Court relies on major judgments concerning the environmental and division of powers. Environment is a shared jurisdiction which brings in the ‘double aspect doctrine” which reflects the idea that the same fact situation can be regulated from different perspectives, one falling within federal jurisdiction and the other under provincial jurisdiction (para 118).

At paragraph 128 Wagner notes:

Nonetheless, while both levels of government may have the ability to regulate different aspects of a given project, one level’s jurisdiction may be broader than the other’s. Recognizing that an activity is primarily regulated by one level of government highlights the fact that the pith and substance of any legislation enacted by the other level of government must be tailored to the aspects of the project that properly fall within the latter’s jurisdiction (emphasis mine).

The Chief Justice rejects Canada’s argument the legislation is constitutional because 1) he rejects the claim that the “effects within federal jurisdiction” aligns with federal legislative jurisdiction and 2) the “effects within federal jurisdiction” aligns with federal legislative jurisdiction (para 135-136). However, the Chief Justice notes the “fact that a project involves activities primarily regulated by the provincial legislatures does not create an enclave of exclusivity” (para. 142). Moreover, “the jurisprudence and academic literature make plain that a low threshold for the application of an impact assessment scheme is a practical necessity” (para. 143). Indeed, citing a 2001 case, quoting from the Bergen Ministerial Declaration on Sustainable Development -“[w]here there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to prevent environmental degradation” (emphasis mine, para. 145). Despite this, the “designation mechanism’s imperfect focus on federal effects is both practically necessary and constitutionally sound” (para 146).

This ruling departs significantly with many of the points raised by industry and provincial governments as seen in the ABCA opinion.

Section 16(2) (see below) which outlines the mandatory factors (an “open-ended list of factors, all of seemingly equal importance”) for requiring a impact assessment however is too given to the Agency offer broad discretion and demonstrates “ that the matter of the scheme exceeds the bounds of federal legislative competence” (para 150).

| (2) In making its decision, the Agency must take into account the following factors:

(a) the description referred to in section 10 and any notice referred to in section 15; (b) the possibility that the carrying out of the designated project may cause adverse effects within federal jurisdiction or adverse direct or incidental effects; (c) any adverse impact that the designated project may have on the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982; (d) any comments received within the time period specified by the Agency from the public and from any jurisdiction or Indigenous group that is consulted under section 12; (e) any relevant assessment referred to in section 92, 93 or 95; (f) any study that is conducted or plan that is prepared by a jurisdiction — in respect of a region that is related to the designated project — and that has been provided to the Agency; and (g) any other factor that the Agency considers relevant. |

The risk is that projects with little or no potential for adverse federal effects will nonetheless be required to undergo an impact assessment on the basis of less relevant, yet mandatory, considerations (para. 154).

Wagner turns to the constitutionality of the information gathering and assessment phase finding that the very broad factors to be considered in section 22(1) of the IAA because the assessment phase is distinct from the decision-making phase, noting that at this stage the “ federal government is not restricted to considering environmental effects that are federal in nature” (para. 157). Furthermore, as the Oldman case found the federal government may gather information about effects beyond those that fall within federal jurisdiction (para. 159). What matters then is how the information is used in making a decision.

Under section 63, the public interest determination must consider five factors:

| (a) the extent to which the designated project contributes to sustainability;

(b) the extent to which the adverse effects within federal jurisdiction and the adverse direct or incidental effects that are indicated in the impact assessment report in respect of the designated project are significant; (c) the implementation of the mitigation measures that the Minister or the Governor in Council, as the case may be, considers appropriate; (d) the impact that the designated project may have on any Indigenous group and any adverse impact that the designated project may have on the rights of the Indigenous peoples of Canada recognized and affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982; and (e) the extent to which the effects of the designated project hinder or contribute to the Government of Canada’s ability to meet its environmental obligations and its commitments in respect of climate change. |

The trouble with this process according to the Chief Justice is that is transforms what is a determination of whether adverse federal effects are in the public interest into a determination of whether the project as a whole is in the public interest (para. 166). In particular, the notions of sustainability and the assessment of the project as a whole., rather than adverse effects within federal jurisdiction (paras. 167-168).

Critically, and this will doubtless come into play in future battles, the Act allows the federal decision-maker to “blend” in effects outside federal jurisdiction such and the projects’ anticipated GHG emissions. This would enable the federal government in a sense to leapfrog using a federal head of power like fisheries to extend decision-making into long-term sustainability (para. 172). This usage could be valid if project fell under a head of federal power such as interprovincial railways (para. 173).

A key problem with the legislation is the expansive definition of environment which allows public interest determination on the basis that a project emits GHGs that flow across provincial and national borders (para. 184). Wagner also pointed specifically to the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act case which noted ““[a]ny legislation that related to non-carbon pricing forms of greenhouse gas] regulation — legislation with respect to roadways, building codes, public transit and home heating, for example — would not fall under the matter of national concern” (para. 186). The Chief Justice observed that the Government of Canada has made no effort to apply the clarified national concern framework in the GGPPA decision to develop a “new and broader matter of national concern” (para. 189). Federal Justice lawyers have their homework cut out for them to make the cases for regulating GHG emissions, not simply pricing them.

Wagner then goes on to describe the negative effects of section 7 “indefinite prohibitions” that are indifferent to the magnitude of the adverse effects (paras. 193-203).

Projects ought to be designated based on their potential effects on areas of federal jurisdiction because, as I have explained, requiring definitive proof of such effects would put the cart before the horse. At the assessment stage, it would be both artificial and uncertain to limit the factors that can be considered to those that are federal. But, for the scheme to be intra vires, its main thrust must be directed at federal matters (para. 206).

In the next post, I will examine the dissent by Justices Jamal and Karakatsanis.

General Observations looking forward

Several observations however can be made. The next case, presumably on the clean electricity regulations, will be heard by a full court with an additional Ontario justice, Madame Justice Michelle O’Bonsawin and former Alberta Court of Kings’ Bench Chief Justice Mary Moreau. Justice Mary Moreau Source: Supreme Court of Canada

Justice Mary Moreau Source: Supreme Court of Canada

Secondly, the court has invited federal Justice to make a case for why regulating the quantum of GHG emissions is of national concern.

Thirdly, a corollary argument could be made that, given that regulatory failure by both the Alberta Energy Regulator and Alberta’s Department of Environment, federal assumption of responsibility under a national concern doctrine may have merit. For a detailed analysis on why this issue may have some merit go to the recent School of Public Policy paper by Drew Yewchuk, Shaun Fluker, Martin Olszynski entitled “A Made-in-Alberta Failure: Unfunded Oil and Gas Closure Liability.”

And finally, the notion of the cumulative impacts of this failure (e.g. tailings ponds, orphan wells,etc.) require national attention. Although courts make decisions irrespective of popular opinion, they have accepted climate change is an existential issue governments must grapple with.

Related Posts

Alberta 4- Canada 1: Alberta Court of Appeal on the Impact Assessment Act