Updated on 2 August 2023

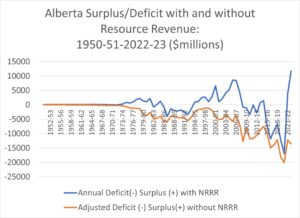

Despite a record surplus reported for last year, the Alberta government only achieves surpluses by counting the royalties from the sale of non-renewable resources (non-renewable resource revenue- NRRR) like ordinary revenue. But does this practice- commenced in the 1940s- faithfully represent the fiscal position of the government?

If the Government of Alberta adopted the private sector’s approach to the sale of physical assets, Alberta’s fiscal history would be decidedly different. Private sector accounting would establish the oil, gas, and bitumen resources as an asset on the provincial balance sheet. The accounting entry would represent the value of all the resources in the ground that would be produced in the current fiscal year and into the future. The value of these assets would be heavily influenced by the estimates made by the government of oil and natural gas prices in future years. When the physical asset is sold, its per barrel recorded or balance sheet value is compared with the royalties, etc. received and only a gain or loss on receipts from the barrels produced by private operators under government license would be added or subtracted from revenue, not the full amount of cash received from the industry.

A private sector example may help to clarify. Company A builds a plant and records the value of the plant on its balance sheet. The plant is an asset because it is expected to generate future revenue. The plant’s value also depreciates as machines and the physical assets degrades. Upgrades would add to the depreciated book value. If Company A decides to sell its plant, it would hope to sell it for more than its carrying value or book value. If the plant sells for more than its depreciated book value, a gain on sale is recorded being the difference between the cash proceeds and the book value of the assets.

Oil and gas reserves “deplete” like plants depreciate. Once the natural resource is sold it is gone forever. That is why receipts from oil, natural gas, and bitumen royalties and the sale of leases are termed non-renewable.

The probable reasons why the provincial government included both the license fees and royalties into General Revenue each year are:

1) that the cash receipts are easily traceable;

2) this policy avoids a) detailed annual work on what reserves have been added through new discoveries and b) the difficult work of determining the future course of oil and natural gas prices- prices which are completely outside the control of the government. However, what is in the province’s control, at least until recently, is the pace of development, Governments and industries have a common and joint interest in ever-increasing production. This is why the Alberta state is so adamant about production cutbacks which would, over time, change Alberta’s fiscal situation from a rentier government to one which will be faced with serious challenges to fund government programs without significantly raising personal and corporate income taxes and implementing a sales tax. These options however are seemingly shut off now given proposed legislation to require referenda to raise personal or corporate income taxes (discussed below).

Nevertheless there were three major components of NRRR recorded and taken into revenue in the post-Leduc oil and gas development period. These three sources were:

- fees and rentals from petroleum and natural gas,

- royalties from petroleum and natural gas, and

- purchase price for leases.

Had for example the government chosen to treat one of the three sources of revenue as annual revenue for example fees and rentals and perhaps purchase prices of leases, then it could have begun saving royalties “for future generations” as Peter Lougheed intended when he established the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund.

Resource royalties are the only reason that Alberta governments can report surpluses and can, seemingly, afford to lower taxes. The capacity to keep taxes low or even reduce them is a huge advantage for incumbent governments.

Since the fiscal year 1950-51, the Alberta government has only recorded five surpluses when resource royalties are excluded and those surplus years were from 1950-1955. Since fiscal 1955-56 the province has never been able to achieve any surpluses unless the resource royalties are taken into government revenue.

But is the continued reliance on volatile royalties sound fiscal policy? If not, what are the provincial government’s alternatives?

Dependence on Resource revenue

According to Alberta Energy and Minerals non-renewable resource revenue (NRRR) comes from companies leasing “the right to explore mineral rights through land sale bonuses, and then pay royalties to the province on a share of the resulting production.” Going back to the early 1950s, Alberta’s Public Accounts reveal that NRRR was a leading source of revenue to the provincial government. For example, in 1950-51, license fees and revenue under the Petroleum and Natural Gas Act produced $9-million, purchase price for leases yielded $28-million and royalties $4.7-million. This total represented represented one-third of government revenue and was enough to pay for the entire education department budget nearly three times over. The purchase price for leases alone would have paid for the entire spending on Public welfare, institutions and charitable grants the largest expenditure of the government at that time.

produced $9-million, purchase price for leases yielded $28-million and royalties $4.7-million. This total represented represented one-third of government revenue and was enough to pay for the entire education department budget nearly three times over. The purchase price for leases alone would have paid for the entire spending on Public welfare, institutions and charitable grants the largest expenditure of the government at that time.

Indeed in 1950-51, NRRR represented three times the take from taxes. At that time, Alberta collected no income tax and the largest source of taxes came from the gasoline and fuel tax. Another huge source of income for the government was from the sale of vehicle licenses. If these sources of revenue are added with NRRR, fully 47 per cent of revenue came from the powerful oil and automotive businesses, including Alberta’s car dealers. And notably the budget of the Alberta Highways department was one of the biggest expenditure departments consuming 15.5 per cent of total government expenditures in 1954-55.

Fast forward to 2022-23 and we find that NRRR also represented one-third of government revenue. Unlike the early 1950s, royalties were by far the largest portion of NRRR constituting 97 per cent with leases, rental and fees a small fraction of total revenue. Of royalties, bitumen was by far the largest earner for the province representing 69 per cent of NRRR. The $25.2-billion in NRRR was sufficient to fund the province’s largest could almost pay for the health department budget of $25.5-billion- but not as many times over, as in 1950.

In terms of NRRR versus other taxes, NRRR was almost two times larger than personal income taxes and nearly five times larger than other taxes including the education, tobacco and cannabis, and fuel taxes. NRRR was also three times the size of corporate income tax revenues, a significant portion, possibly twenty per cent of which come from oil producers and refiners.

Over time

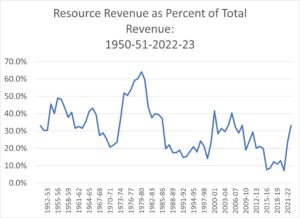

As the chart below illustrates, over the past 70 years, non-renewable resource revenue has fluctuated between 7 per cent (2020-21) to 64 per cent (1979-80) of total government revenue. Alberta taxpayers therefore enjoy low taxes and no sales tax because the oil industry pays a meaningful share of government spending. These figures do not include corporate income taxes paid nor the personal income taxes of oilpatch workers.

Resource revenue reliance and fluctuating oil prices have always been a huge problem for long-term budget planning. As some have observed, this reliance or over-dependence on NRRR is similar to crack cocaine’s addictions.

Legacy of ignored policy advice

Sales tax the obvious choice

A provincial sales tax (PST) or a PST harmonized sales tax (HST) with the federal goods and services tax (GST) is the most obvious candidate to reform Alberta’s revenue structure. It’s advantages include:

1) Alberta could easily impose a sales tax of up to 5 percent and still remain the lowest taxed jurisdiction in Canada;

2) less of the revenue from a sales tax goes towards administrative costs. He also points out that a sales tax is hard to avoid;

3) it can capture inherited wealth used to consume in the province and spending by visitors to the province;

4) its political implementation difficulties could be mitigated somewhat by not using a PST as a way to reduce CIT and by implementing a refundable tax credit directed at low-income individuals and families; and

5) perhaps most importantly, a sales tax is a far more stable source of revenue than the CIT, PIT, and non-renewable resource revenue on which the province currently relies.

Over the years attempts have been made to educate elected officials (politicians) about the dangers of over-reliance on VOLATILE resource revenue. These efforts followed the acceptance by the Klein of free markets what some have termed “neo-liberalism.” This philosophy was practiced by Ronald Reagan who was known for cutting taxes, starving the state and firing air traffic controllers.

In Ralph Klein’s government, this influence came directly from the mouth of New Zealand’s Sir Roger Douglas. Douglas was a minister in a Labour government who re-engineered the government by selling off Crown assets, cut regulations, and running government like a corporation.

Some of these ideas were reflected in the Financial Review Commission undertaken for Klein and chaired by TransAlta’s former Chairman Marshall Williams. But a key turning point was the March 1994 conference in Red Deer organized by Alberta Treasury and co-chaired by Treasurer Jim Dinning and University of Calgary President. On the matter of revenue collection while six of ten tables either supported a sales tax or temporary sales tax. According to former Deputy Treasurer Al O‘Brien, this idea was quietly shelved.

Then in 1994, a report by the Alberta Tax Reform Commission acknowledged that a sales tax would form part of an “ideal” tax mix. The politicians’ response? To pass the 1995 the Alberta Taxpayer Protection Act which required a referendum be passed to implement a sales tax- an election promise which took some time to introduce.

Still, unease percolated through academic halls and senior levels of the provincial bureaucracy. In 2000, UofC economist Kenneth McKenzie authored a monograph for the Canada West Foundation entitled “Replacing the Alberta Personal Income Tax with a Sales Tax.” In a 2022 chapter, McKenzie recounts his 2003 meeting in Premier Klein’s office in which Klein claimed to have read the paper saying he was “personally sympathetic to having a conversation about the idea…. but politically he couldn’t commit.”

At about the same time, a conference largely made up of academics and public servants was held to discuss Alberta’s volatile revenue with proceedings published by the Institute for Public Economics (IPE) at the University of Alberta. In published proceedings called Alberta’s Volatile Government Revenues: Policies for the Long Run, many leading Alberta and Canadian economists due attention to Alberta’s revenue vulnerability.

I was remiss in not referencing an important contributions about Alberta’s fiscal vulnerability found in Canadian Public Policy vol 6 supplement, Feb 1980 stemming from important papers given at a conference on the Heritage Fund the previous year. Authors included Brian Scarfe, Tom Powrie, Mel McMillan, Robert Mansell, Allan Tupper, Larry Pratt, Mike Percy, Ken Norrie, and Roger Smith.

In 2002, as gas prices soared, and the government was again running massive surpluses, a Financial Management Commission (FMC) was established to provide advice to the government to do with the surpluses. The FMC observed the government needed to reduce the province’s reliance on NRRR. In 2000-01, NRRR had accounted for 41 per cent of revenue. Except for tucking NRRR away into various accounts- like the Stabilization Fund and Debt Retirement Account- above certain legislated levels, nothing was done about the dependency issue rather than “just manage” it.

In 2009, the Premier’s (Stelmach) Council for Alberta’s Economic Strategy report admonished the almost sacred Alberta lax Advantage. It was a rather daring shot across the bow of the Tories’ claim to be good fiscal managers. But nothing changed except for a series of three new PC premiers who kicked the decision further down the road.

For more detail on these reports visit my chapter 1, pp. 32-40 and Ken McKenzie’s chapter 9, pp. 163-169. A Sales Tax for Alberta- Why and How

Further efforts in the academy included a 2010 IPE conference called “Boom and Bust Again-Policy Challenges for a Commodity-based Economy,” which featured papers from Herb Emery and Ron Kneebone and Bev Dahlby, Katherine Masapac and Mel MacMillan.

Other more recent efforts to advance the cause for considering a sales tax was Professor Jack Mintz’s 2011 Eric J. Hanson memorial lecture entitled “The VAT as game changing tax policy in the U.S. and Alberta contexts.” In 2013, Ergete Ferede’s IPE paper “The Response of Tax Bases to the Business Cycle: The Case for Alberta and an IPE seminar on a sales tax in January 2015 featured speakers from both sides of the argument.

Up until the present, the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy (SPP) initially under the direction of Jack Mintz wrote and oversaw a multitude of papers on tax policy, more recently supporting the idea of lowering corporate income taxes which were featured in the UCP’s 2019 election victory.

Throughout the 2000s and 2010s there were occasional trial balloons thrown out by Alberta finance ministers concerning a discussion on a sales tax but these efforts were quickly rebuffed by premiers and walked back by the ministers. (For details see Graham Thomson’s excellent chapter 2 in A Sales Tax for Alberta- Why and How).

By the end of the 2010s, it had become well accepted political article of faith that the words “political sales tax” would not be mentioned in political company. By the early part of the accidental NDP government was already distancing the PST with Joe Ceci opining the tax is “the one we do not name.”

All these efforts., except for lowering corporate income taxes, have been met with indifference in political circles. Yet in 2020, Danielle Smith seemingly broke new ground by stating in wrote in a September 2020 Postmedia that op-ed Albertans should basically suck it back and pay a sales tax. This op-ed was followed by an invitation from the SPP to write an SPP paper entitled “Alberta’s Key Challenges and Opportunities,” while she was at the Alberta Enterprise Group. In the article she stated that the economic problem for the Alberta government was not the need to diversify its economy but to diversify its revenue.

Other than The Globe and Mail and occasional op-eds advocating a PST or harmonized sales tax, only the Liberal Party of Alberta would entertain the concept.

Then in July 2022 less than a year from the May 2023 election A Sales Tax for Alberta-Why and How was released into an un-receptive market with no mainstream media interest and a paucity of reviews.

A more disturbing issue though is the evident indifference inside the Treasury Board and Finance Ministry (bureaucracy) to the question of a sales tax as an addition to current revenue structures. In a FOIPP request to five key divisions of Treasury Board and Finance, including the deputy minister’s office and the minister’s correspondence unit, no records (notes, media articles, emails, memos, reports, letters, graphs, tables, briefings, whether written, photographed, recorded or stored in any manner pertaining to a provincial sales tax for Alberta) were found for the two years between 13 March 2021 to 13 March 2023. This means this central government agency was not monitoring media for articles, websites, academic journals or books respecting a sales tax. It is almost impossible to believe that no Albertan had written the finance minister about this topic over that time period. It would therefore appear that by the beginning of the May election that conversation about a sales tax had been suppressed in the bureaucracy as well as the mainstream media and the of course politicians fearful of uttering these three words.

It will get much worse

The current climate for a PST is even more hostile as the Alberta Taxpayers’ Protection Act will be amended to tie the finance minister’s hands even more tightly by requiring referendums if the government intends to increase either personal or corporate income tax. This promise was made during the election campaign and is contained in the mandate letter to Alberta’s finance minister Nate Horner.

All steps are nearly in place to strangle government programs by vitiating any ability for the finance minister to fund programs from new revenue sources except going to central Canadian or foreign investment bankers.

Is this enlightened and sustainable fiscal policy in an economy where, increasingly, the long-term viability of fossil fuel production is being called into question?

As this timeline shows, it is not for lack of trying that I and may others had attempted to influence public policy and to warn of the dangers of excess dependence on a single source of revenue.

Recommended summer reading

The books’ authors represent a diversity of settler and indigenous perspectives. This is a critical historical analyses of the roles of the federal and provincial governments and extractive industries who have little respect for treaties between them and First Nations.

The books’ authors represent a diversity of settler and indigenous perspectives. This is a critical historical analyses of the roles of the federal and provincial governments and extractive industries who have little respect for treaties between them and First Nations.

This early 21st century riff on Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield is a first hand account of West Virginia life after the coal mines are out of business. It is a deeply compelling account of the son of a drug addict’s for twenty years of a dark foster care system, love of family, and how Purdue Pharma targeted this region of physical pain with its Oxycontin product. Kingsolver presents a sympathetic picture of the West Virginia trailer tribe who are viewed by outside elites by a litany of epithets including deplorables.

This early 21st century riff on Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield is a first hand account of West Virginia life after the coal mines are out of business. It is a deeply compelling account of the son of a drug addict’s for twenty years of a dark foster care system, love of family, and how Purdue Pharma targeted this region of physical pain with its Oxycontin product. Kingsolver presents a sympathetic picture of the West Virginia trailer tribe who are viewed by outside elites by a litany of epithets including deplorables.

A more challenging book by Katharina Pistor, a professor of law at Columbia University, examines the origins and character of legal codes which have protected private property whether land, industrial capital, bank loans, debt instruments, or intellectual property. Durability, stability, and security of capital is coded into complex legal agreements and laws and regulations which enable the reproduction of capital. The book tackles the widening wealth gap between the holders of capital and everybody else.