Earlier this year I was asked to contribute a paper on Alberta’s public debt to the School of Public Policy’s Alberta Futures project. My particular subject was “Alberta’s Public Debt: Entering the Third Crisis.” The questions I attempted to answer included:

When has government borrowed too much?

What will rapidly rising debt levels mean for Alberta taxpayers?

What are the critical debt thresholds for the Province?

What role will credit rating agencies play as they evaluate debt thresholds in relation to those in other provinces?

What do higher debt levels mean for the Alberta Tax Advantage and Alberta’s long-term economic growth?

What role does the federal government play in monitoring provincial deficits and debt levels?

For the analysis, I went through over 100 years of Alberta’s public accounts which were digitized by the University of Alberta’s Libraries. It was fascinating to read the earliest details of Alberta’s initial entry into Canadian and foreign debt markets. What became clear is that over the past 120 or so years Alberta has worked through two debt crises (1936, 1993) and is entering another period of fiscal stress.  Each period includes a debt accumulation phase followed by a form of crisis and concludes with a paydown of the debt. In the first instance, the phase lasted from 1905 until 1955. The first phase of debt accumulation resulted in a debt default, followed by ten years of non-payment, a debt restructuring and paydown of debt from a booming oil and gas economy.

Each period includes a debt accumulation phase followed by a form of crisis and concludes with a paydown of the debt. In the first instance, the phase lasted from 1905 until 1955. The first phase of debt accumulation resulted in a debt default, followed by ten years of non-payment, a debt restructuring and paydown of debt from a booming oil and gas economy.

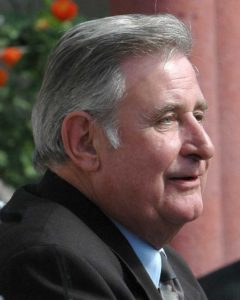

Premier William Aberhart

Source: Wikipedia

In 1993 after about a decade of debt accumulation, Alberta was facing another debt crisis. It could certainly be argued that the crisis was manufactured, however the quantum of debt accumulated caused a fiscal tightening and eventual quick debt paydown when natural gas and oil prices were high. The current phase began just over a decade ago and after growing deficits, the UCP government is largely following the playbook of Ralph Klein and Jim Dinning- “we have a spending problem, not a revenue problem.” How this third debt crisis resolves itself is anyone’s guess.

Each phase of every cycle is associated with the rise and fall of commodity prices. In the first period it was wheat; the second cycle was oil and natural gas prices. The current cycle is largely driven by prices for bitumen.

The technical aspects of the paper include the development of a 115-year data set including major direct and indirect liabilities and financial assets of the province.

The figure from the paper below shows the quantum of debt as a percentage of provincial GDP.

Environmental liabilities

In addition to analyzing the provincial public accounts, I considered the question of who is going to pay for the huge unfunded environmental liabilities for oil and gas wells, pipelines and oilsands facilities and tailings ponds. The cost of addressing these liabilities is gaining more and more notoriety with bankrupt firms walking away; municipal governments stiffed for taxes; and significant federal and provincial taxpayer assistance to begin the massive clean-up.

Source: CBC.ca

This issue will become an increasing factor to consider by rating agencies. it will also become a point of tension between Alberta and the federal government.

Answers to questions:

When has government borrowed too much?

The short answer is the public will not know until the Government finds it can no longer borrow. A famous Ernest Hemingway quote when asked how he went bankrupt goes: “Two ways. Gradually, then suddenly.”

What will rapidly rising debt levels mean for Alberta taxpayers?

Rising debt levels will produce escalating debt servicing costs, alongside more debt issuance, especially if (when) interest rates rise. This will put pressure on the government to raise taxes, possibly including a sales tax and higher fees for

government services.

What are the critical debt thresholds for the Province?

There are no fixed indicators which definitively mean that a government can no longer borrow. There is an array of unpredictable factors that are national and international and outside the Alberta government’s control. For example, what

happens if the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar, no longer performs its function? ….. Alberta is near some sort of debt threshold, though there is some uncertainty precisely how near.

This seems to me somewhat glib. With oil and natural gas prices recovering, the UCP government has a bit more breathing room. Still the overwhelming force of climate change adaptation implies that production and the price of fossil fuels will fall over the next three decades. Whether hydrogen and carbon capture extend this period is hard to evaluate.

What role will credit rating agencies play as they evaluate debt thresholds in relation to those in other provinces?

Rating agency opinions (will continue to) reflect their vantage point as experts who compare the creditworthiness of sub-national debt. Agencies’ analytical capacity to dissect a government’s accounting systems, knowledge of the underlying drivers in a government’s capacity to manage its finances, combined with an international perspective are important factors in their evaluation.

What do higher debt levels mean for the Alberta Tax Advantage and Alberta’s long-term economic growth?

Higher debt levels mean that Alberta’s tax advantage will become difficult to sustain. The Government’s narrative that Alberta is an expenditure outlier is being displaced by a growing public awareness that Alberta is also a revenue outlier.

What role does the federal government play in monitoring provincial deficits and debt levels?

The recent financial stress in provincial funding in March and April 2020 involved central bank purchases of provincial securities. This action suggested some provinces, notably Newfoundland,14 were facing difficulties borrowing (Drummond, 2021; Hanniman, 2021).

Ottawa is looked to by rating agencies as a critical backstop when provincial credits are nearing exhaustion. The mandate of the central bank to buy provincial securities has been long established as the rating agencies judgement that the federal government would ultimately act to avoid a default.

My conclusion:

The current fiscal crisis is similar to previous crises because prices for Alberta’s principal export commodities have fallen and prospects for a recovery are increasingly uncertain. In addition, the expansion of oil sands is much in doubt, reducing the large capital investments which have driven economic growth and development over the first decade and a half of the 21st century. Grave uncertainty about future economic prospects, possible legal challenges to how the oil industry has been regulated and the environmental consequences of oil and bitumen extraction, will mount. These issues are tantamount to the reputational risks of the Province as a debt issuer.

Although industry is responsible for reclaiming properties damaged through resource extraction, there is considerable doubt as to the adequacy of financial security pledged for reclamation and the capacity and willingness of industry to pay for oilsands remediation (Auditor General of Alberta, 2015, 25-33, 2021, 29-34). The uncertainty of who will pay will emerge as a critical issue for the Province’s credit rating and its credibility as a steward of Alberta’s natural endowments.

The paper made two policy recommendations:1) issue of oil indexed bonds where the interest rate would vary according to a predetermined scale of oil prices. This would require the province to pay higher rates of interest when oil prices are high and the province is capable of doing so. 2) Establish a statutory requirement to pay in a certain percentage of every debt issue to assure repayment at maturity. This was common up until the 1960s but is now unfashionable. The recommendation however would force provincial cabinets to make difficult budgetary choices (i.e., cut spending or raise taxes) earlier.

In my judgement there is still too much enthusiasm to restore a savings fund when oil and gas prices recover. This strikes me as naïve and untenable under current circumstances. Given the dim prospects for non-renewable resource revenues, Alberta politicians should think twice about whether maintaining a Heritage Fund, let alone plowing more money into it especially after the disastrous VOLTS strategy, makes sense.

This paper considers an economy in which policymakers with different preferences alternate in office as a result of elections. Government debt is used strategically by each policymaker to influence the choices of his successors. If different policymakers disagree about the desired composition of government spending between two public goods, the economy exhibits a deficits bias; that is, debt accumulation is higher than it would be with a social planner. The equilibrium level of debt is larger the larger is the degree of polarization between alternating governments and the less likely it is that the current government will be re-elected. Founded in 1933 by a group of young British and American economists, The Review of Economic Studies aims to encourage research in theoretical and applied economics, especially by young economists. Today it is widely recognised as one of the core top-five economics journals. The Review is essential reading for economists and has a reputation for publishing path-breaking papers in theoretical and applied economics.