Updated 18 May 2021

On 25 March 2021 Canada’s Supreme Court issued arguably its most crucial judgment in a decade.

The case arose from three appeals from the high courts of Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan respecting the constitutionality of the Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (GGPPA). Challenges of the GGPPA were made to the legislation by the Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan government in their various jurisdictions. In Ontario and Saskatchewan the courts of appeal sided with the federal government while the Alberta Court of Appeal ruled against the constitutionality of the GGPPA. While the jurisprudence within the case will be cited for generations, it is difficult at this stage to assess the long-term consequences on the future balance of the Canadian federation.

The winners were the federal Attorney General and the numerous environmental and indigenous groups representing most of the intervenors for the federal position. The losers were the governments of Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan who challenged the constitutionality of the GGPPA. Appendix A below is a list of the dozens of organizations involved in the litigation.

Background

For the past quarter century governments and courts have been struggling with “what to do” about environmental “issues.” Closely aligned to this question has been the Crown’s relationship to First Nations. As scientific evidence has strengthened the case for urgent action on slowing the release of GHGs into the atmosphere, Alberta’s fossil fuel industry has faced calls to reduce its GHG emissions. Amid confusing signals from Ottawa over the past quarter century (accommodative tax policy changes in late 1990s for the oilsands, purchase of the Trans Mountain Pipelines, cancellation of Northern Gateway, and moratorium on west coast shipping), the Alberta government has consistently acted to defend its principal economic driver.

Supreme Court judgments over the past decade have tended to side with First Nations and against polluters (e.g. Redwater decision). There is also emerging a growing consensus that governments must act NOW to address climate change or the requirements for even more coercive actions by governments will be required, including serious limitations on the behaviour of individuals and corporations.

The Result

The 404-page, 616-paragraph ruling will have a profound impact on the fossil fuel consumption patterns of all Canadians and Canadian businesses. The decision with its highly technical, constitutional analysis will be inaccessible to 99 per cent of the population and meaningful to constitutional scholars and lawyers, jurists, corporate counsels, environment and energy department policy analysts. Few politicians, including many first ministers will not read the full judgement relying on their Attorney Generals to distill the meaning.

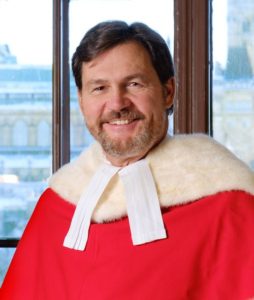

In the majority ruling, written by the Chief Justice Richard Wagner, the Act is found to be constitutional or within the competence of the federal government. The judgment relied on a broader reading of the peace order and good government clause in the Constitution Act, 1867, known as a residual power of the federal government. Wagner’s majority period was concurred in by Justices Abella, Moldaver, Karakatsanis, Martin and Kasirer. Vigorous dissents came from Justices Cote, Brown, and Rowe.

The majority opinion means that the backstop mechanism under the Act which empowers the federal cabinet to institute a GHG pricing scheme in provinces where no suitable pricing schemes exist may continue to exist. While the withering dissent of Brown against the “majority” was very tightly argued, it did not satisfy the pragmatism of his fellow jurists who accepted that climate change was an existential issue and in the absence of serious progress justified the federal government’s carbon pricing scheme.

Issues

For Justice Côté, her dissent addressed palpable concerns of the federal Cabinet abusing powers granted by Parliament. Côté argued that the extraordinary and broad powers granted the federal Cabinet – the how of the legislation- was unconstitutional. Côté held that:

provisions in the GGPPA that permit the Governor in Council to amend and override the GGPPA violate the Constitution Act, 1867, and the fundamental constitutional principles of parliamentary sovereignty, rule of law and the separation of powers…..provisions in the GGPPA that permit the Governor in Council to amend and override the GGPPA violate the Constitution Act, 1867, and the fundamental constitutional principles of parliamentary sovereignty, rule of law and the separation of powers. (Page 27)

The Chief Justice however made the case that the authority of the federal cabinet was effectively circumscribed by the purpose of the Act. This did not satisfy Justice Brown who, in his dissent, worried that Part 2 of the GGPPA constituted

a deep foray into industrial policy, also falls within matters of provincial legislative authority granted by s. 92(10) over local works and undertakings. Also relevant to Part 2 of the Act — with its emphasis on heavy industrial emitters, trade exposure, and international competitiveness — is s. 92A. This head of power gives the provinces the exclusive jurisdiction to make laws in relation to the exploration, development, conservation, and management of non-renewable natural resources in the province (Emphasis added- Para 346).

While the majority were comfortable that for policy reasons, carbon leakage, provinces were incapable of addressing the existential crisis, Justices Brown and Rowe argued that the Attorney Generals of British Columbia and Canada and the majority had failed to satisfy various legal precedents which had considered the “national concern” doctrine. Justice Rowe emphasized the fact that provinces had numerated powers under the Constitution Act to regulate the pricing of GHG and national concern or provincial inability could not be used to justify federal intrusion. Both Brown and Rowe dismissed the Chief Justice’s view that the “pith and substance” of the GGPPA was the “reduction of GHG emission by pricing emissions in a manner that distinguishes among industries based on emissions intensity and trade exposure” (Para 340).

Mr. Justice Malcolm Rowe, who resided in Newfoundland and Labrador and Justice Brown who taught law at the University of Alberta prior to their elevation to the high court, also expressed worry that federal regulations could harm or shut down particular industries. According to Justice Russell Brown:

Further, poised as they are to affect the cost of fuel and dictate the viability of emissions-intensive trade-exposed industries, the charges imposed by the Act stand to have a profound effect on provincial jurisdiction and the division of powers (Para. 392).

Further:

the examples given by the majority of how a regulation may fail to conform to the purposes of the Act are not enlightening. For example, the majority posits that federal Cabinet “could not list a fuel . . . that does not emit GHGs when burned” (para. 75). That may be so, but what the majority might also have wished to consider is the obvious possibility that the federal Cabinet will discriminate against provinces or industries in a way that has nothing to do with “establishing minimum national standards of GHG price stringency to reduce GHG emissions (Emphasis added- Para 412).

Justice Rowe, in preparing the groundwork for future challenges of regulations under the GGPPA, noted:

To establish “minimum national standards”, any differences in treatment between industries or provinces in the regulations must be justified with respect to “price stringency to reduce GHG emissions” (Chief Justice’s reasons, at para. 207). Regulations that have the effect of favouring or imposing unequal burdens on certain provinces and industries in a manner that cannot be so justified would-be ultra vires the division of powers (Emphasis added- Para 589).

Another issue is the matter of justifying federal jurisdiction with the use of emergency powers. The Chief Justice for the majority found that following the well-established tests in the case law found the GGPPA fell under the residual power of POGG and the national concern doctrine. In other cases, federal jurisdiction was upheld using the so-called emergency powers. Jurisprudence is clear that an emergency is not required to invoke the national concern doctrine. This question was canvassed at some length by Justice Brown:

It is curious that the majority does not consider this, since its reasons speak in such terms. What will describing climate change as “an existential challenge[,] a threat of the highest order to the country, and indeed to the world” (para. 167; see also paras. 187, 190, 195 and 206). Further, the emergency branch’s requirement of temporariness means that the majority’s unconstitutional transfer of jurisdiction from the provinces to Parliament would do less damage to Canadian federalism, and for less time, lasting only until this crisis passes (Emphasis added- Para 399).

In other words, while the Act does not come with a “best before” date, it does contemplate an end. And while at the outset of an emergency it will often be difficult or impossible to identify with any precision when it might end, the emergency branch has been applied in circumstances where it is reasonably apparent that the emergency will, at some point, end. Indeed, the point of action is presumably to do what is necessary to ensure that the emergency will end (Para. 300).

Brown goes on to chastise Canada’s Attorney General for not doing “the necessary (or any) work to show that Parliament justifiably relied upon its emergency powers (Para 401).

The result of the judgment is the legislation was found to be within the power of Parliament. This means some stability and uniformity to pollution pricing across Canada.

Another important issue reviewed by the Court was the question of whether the pricing scheme was a form of taxation. The Court was satisfied the charges were regulatory in nature.

Opinion

Time will tell if the legitimate concerns of Justices Côté, Brown, and Rowe are realized. One might contemplate that at some future date, in the absence of progress to reduce in absolute terms and in a meaningful way Canada’s high per capita GHG emissions, Parliament may be forced to resort to emergency powers on a temporary but more comprehensive basis, to deal with climate change as an emergency.

It is to be hoped that this setting of minimum national standards will not open the door to a wholesale invasion of provincial jurisdiction through the creation of minimum national standards. There is controversy already over how even-handedly the federal Cabinet has been in exempting certain provinces (e,g, Quebec) from the pricing scheme.

In general terms, though, the ruling once again shows the pragmatism of the Court to arrive at a reasonable middle ground. There will naturally be a whole industry and literature springing up around this landmark decision, with constitutional purists finding the Court has deviated from the stare decisis pathway forged by the Court’s predecessors. Given the clear articulation of the view that the Governor in Council cannot constitutionally enact regulations which deviate from the Act’s purpose, the federal Cabinet likely will stay within the purposes of GGPPA.

To most observers’ surprise, the Alberta Premier admitted that no groundwork had been done to prepare for a losing judgment in spite of the fact that two out of three provincial courts of appeal had supported the federal position. What Alberta does next is anyone’s guess. My hunch is that the Alberta Attorney General will carefully examine Justices Brown and Rowe’s dissenting opinions and perhaps pass a law on GHG pollution pricing that will not be exempted thereby prompting outrage and another constitutional challenge. This approach would be unfortunate as time is of the essence to ratchet down GHG emissions in Alberta, which has the highest per capita emissions in Canada.

APPENDIX A

The Parties

Attorney General of Saskatchewan, Attorney General of Ontario, Attorney General of British Columbia, Attorney General of Canada, Attorney General of Alberta.

Interveners- each organization, group represented by separate counsel

1. Attorney General of Quebec, Attorney General of New Brunswick, Attorney General of Manitoba

2. Progress Alberta Communications Limited

3. Anishinabek Nation and the United Chiefs and Councils of Mnidoo Mnising

4. Canadian Labour Congress

5. Saskatchewan Power Corporation and SaskEnergy Incorporated

6. Oceans North Conservation Society

7. Assembly of First Nations

8. Canadian Taxpayers Federation

9. Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission

10. Canadian Environmental Law Association, Environmental Defence Canada Inc. and the Sisters of Providence of St. Vincent de Paul

11. Amnesty International Canada

12. National Association of Women and the Law and Friends of the Earth

13. International Emissions Trading Association

14. David Suzuki Foundation

15. Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation

16. Smart Prosperity Institute

17. Canadian Public Health Association

18. Climate Justice Saskatoon, the National Farmers Union, the Saskatchewan Coalition for Sustainable Development, the Saskatchewan Council for International Cooperation, the Saskatchewan Environmental Society, SaskEV, the Council of Canadians: Prairie and Northwest Territories Region, the Council of Canadians: Regina Chapter, the Council of Canadians: Saskatoon Chapter, the New Brunswick Anti-Shale Gas Alliance and the Youth of the Earth

19. Centre québécois du droit de l’environnement and Équiterre.

20. Generation Squeeze, the Public Health Association of British Columbia, the Saskatchewan Public Health Association, the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, the Canadian Coalition for the Rights of the Child and the Youth Climate Lab

21. Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs

22. City of Richmond, the City of Victoria, the City of Nelson, the District of Squamish, the City of Rossland and the City of Vancouver

23. Thunderchild First Nation

Related Posts