Updated 2 April 2020

A number of historic events have taken place this past week, with long-term ramifications for the Canadian and Alberta economies.

- Bank of Canada actions to purchase money market paper of provincial governments

- Bank of Canada starts quantitative easing and will purchase commercial paper

- Manitoba Premier calling on the federal government to establish a Pandemic Emergency Credit Facility

- Province of Alberta issues a century bond

Alberta is witnessing the deepest economic storm since the mid-1980s and likely will see conditions similar to the Great Depression over the next few months. Unlike the Great Depression, our social safety net and government willingness to “do whatever it takes” will moderate the financial and economic distress. Unlike the Great Depression, Alberta’s health care system (public and private) will be solely tested. Like the Depression, Albertans have been unwittingly painted into a corner as another commodity price crash reduces cash flow by up to 60 per cent, creating fear in the province’s dominant industry. Like the Great Depression, Alberta’s public finances will come under increasing scrutiny as deficits balloon.

Money market paper of provincial governments

On Tuesday 24 March, the Bank of Canada announced a program to “support the liquidity and efficiency of provincial government funding markets.” The Bank will purchase up to 40 per cent of each provincial money market securities with terms of 12 months or less. The Bank reserves the right to adjust the 40 per cent limit “if market conditions warrant.”

The first issues purchased on 25 March totalled $279 million and Thursday’s purchases were $121 million. The goals of the program are to “support a liquid and well-functioning market for short-term provincial borrowings.“ Although the Bank publishes the quantity of provincial securities purchased, it does not reveal the name of the provincial borrower.

The Province of Alberta’s borrowing program includes a domestic promissory note program. The issue size of the program is “flexible” and minimum denomination of these Notes are $100,000. In Budget 2020, it was reported that short-term borrowing (less than one year) was about $7 billion with nearly all debt maturing within 90 days.

Purchase of Commercial Paper

Another central bank initiative was its decision to purchase commercial paper to “support the ongoing needs of a wide range of firms and public authorities.” These purchases also include Asset-backed Commercial Paper issued by “Canadian firms, municipalities and provincial agencies with an outstanding CP program.” The ABCP to be purchased matures within three months and must be “of sufficiently high quality, broadly equivalent to a minimum short-term credit rating of R-1 (high/mid/low).”

Commercial Paper is an unsecured promise to pay the holder of the note the face value of the note within 90 days. Commercial Paper is issued by large corporations with a credit rating. Alberta’s largest energy companies would be frequent issuers in the market. Given the fall in the oil prices, the current market will be challenging for oil companies and the central bank’s purchase of these type of securities will instill more confidence of institutional investors to re-finance larger companies’ maturing obligations.

Quantitative Easing

On 27 March, the Bank of Canada announced secondary market purchases of Government of Canada securities, in effect, commencing quantitative easing on 1 April. The Bank pledged to purchase a minimum of $5 billion in federal government securities across a range of maturities per week (Incorrectly reported as per month previously). This action is designed to support “the liquidity and efficiency of the government bond market.”

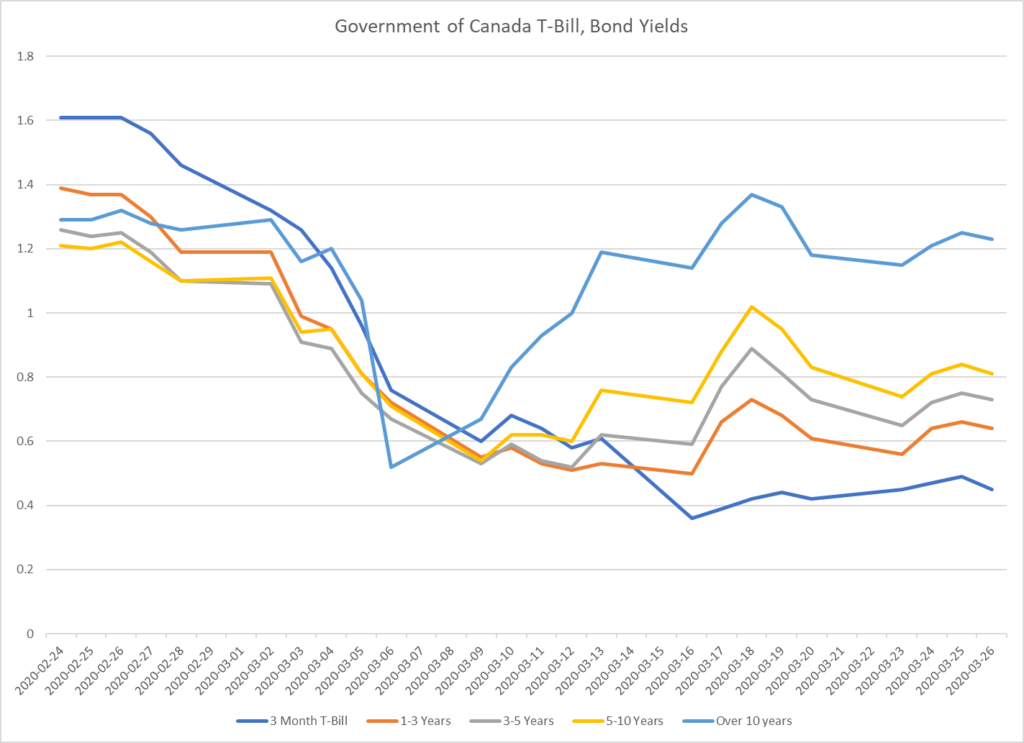

The chart below shows the behaviour of bond yields since the end of February. The chart indicates a sharp rise in bond yields associated with the price cash in oil over the weekend of March 7-8th. As a major oil producer, this shock was transmitted to the government bond market and resulted in rising rates for longer-term.

As the chart above reveals, measures taken earlier, by dropping short-term rates and supplying liquidity to markets, short-term funding costs were kept lower.

Manitoba’s Brian Pallister– Unusual Request

On 26 March, at his daily press conference, Manitoba’s Premier Brian Pallister candidly admitted his provincial government’s fiscal stress. The province had built up a “rainy day fund” of a billion dollars over the past four fiscal years. “Our funds could be gone in three months or less,” Pallister stated. The Premier called on Ottawa to establish a Pandemic Emergency Credit Facility. Under this concept, the federal government would borrow money on behalf of the provinces, saving provincial governments millions in borrowing costs. Right now, the spread between 10-year Government of Canada bonds and Ontario government bonds, the most liquid provincial credit, is over 150 basis points.

Pallister’s suggestion is a temporary expedient to lessen the stress on provincial debt managers’ individual efforts to cope with the liquidity strain. Coordinated borrowing by Ottawa on behalf of provincial governments makes sense at times like these, but requires a provincial acknowledgement (like Pallister) that we need help.

This measure harkens back to the Great Depression when the Dominion of Canada agreed to implement a loan council that would manage the borrowings of provincial governments. The Loan Council modelled after the Australian Loans Council would be comprised of the Bank of Canada, federal Finance and the provincial government. However, the Aberhart government in early 1936 decided not to endorse the idea, abrogating the scheme.

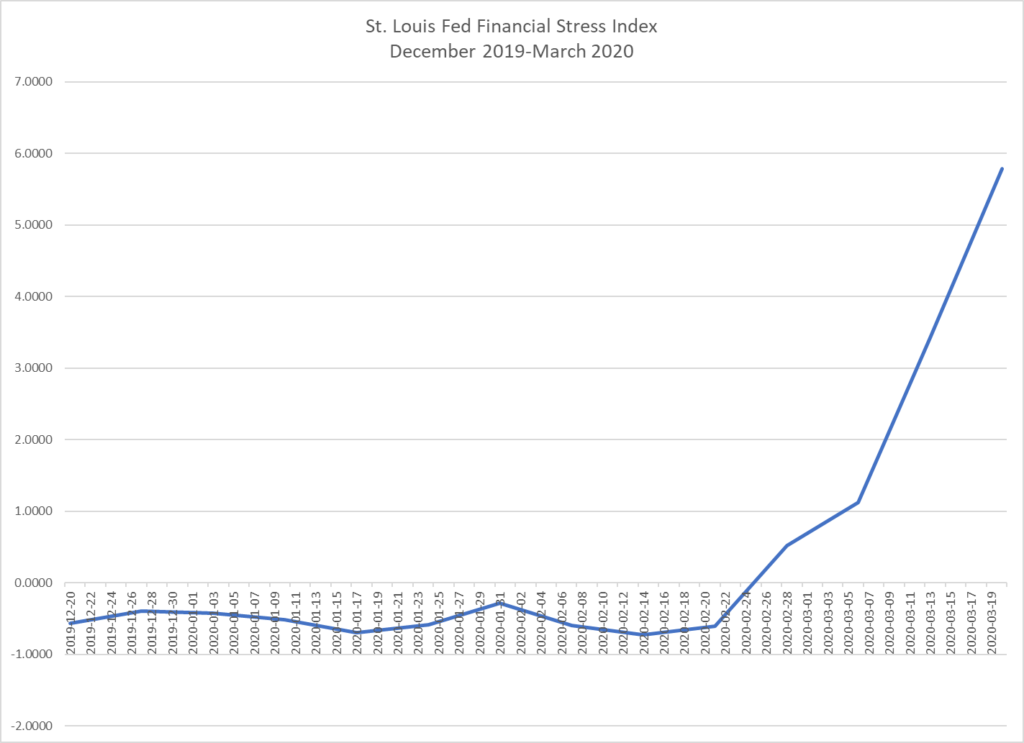

Pallister’s plea comes at a time of enormous stress to the financial system. The St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank publishes a Financial Stress Index which “measures the degree of financial stress in the markets and is constructed from 18 weekly data series: seven interest rate series, six yield spreads and five other indicators. Each of these variables captures some aspect of financial stress.” The chart below shows how the stress erupted shortly after oil prices began dropping precipitously.

Province of Alberta issues century bond

According to BNN Bloomberg, on 24 March Alberta launched a 3.06 per cent century bond maturing 1 June 2120. According to BNN-Bloomberg, the $300 million bond issue was priced at “183 basis points over Canadian government bonds due December 2048. …..Risk spreads between provincial and federal bonds have blown out in recent weeks in the global credit crunch that stemmed from the coronavirus pandemic.”

The issue was placed by the Bank of Nova Scotia and follows a $500 million 10-year domestic issue as well as 260 million Swiss francs of 8-year debt.

According to Budget 2020, Alberta’s borrowing requirements were estimated to be nearly $16 billion with term debt issues of $17.1 billion to refund maturities of $5.3 billion, reduce short-term debt outstanding, and to finance operating, and capital spending. It is safe to assume, borrowing requirements in 2020-21 have increased substantially and will impose strains on the province’s capacity to raise moneys in a cost-effective manner.

Although Alberta still enjoys a good credit rating, borrowing at times of financial stress like the present environment will be doubly challenging given the oil price shock. A key question for Alberta debt managers will be whether the federal government comes out with a significant retroactive fiscal stabilization payment.

In these extraordinary times, cash or liquidity, in the argot of central bankers, is key. Over the course of the next several (?) months, millions of Albertans and Alberta businesses will be relying on the “credit card” of the province and the federal government. With the 28 March announcement of educational assistants and substitute teachers being relegated to federal EI, the provincial government is beginning to examine “non-essential payments” in order to maintain some financial flexibility as it practices triage of its finances.

Such is the drama of decision-making by authorities managing day-by-day, and hour-by-hour. Fiscal outcomes for all segments of the population (what workers and what businesses?) will be closely monitored as they should be. The Alberta government, now with limited fiscal flexibility, will increasingly be looking to Ottawa for financial support. How will the federal “Trudeau” government respond? Perhaps now is not the time to be as demanding as when oil was trading at $60 per barrel?